In her recent letter to the Office for Students, (former) Education Secretary Gillian Keegan recognised “the considerable cultural, societal and economic benefits” generated by our “world-leading small and specialist” Higher Education (HE) providers in creative arts subjects.

In the same letter, she stated that grant funding for high-cost higher education courses in the arts and creative subjects would be frozen next year and that there would be no postgraduate teaching allocation at all to these subjects under the Strategic Priorities Grant, or SPG.

This announcement has sparked heartfelt protests and articulate petitions for the creative arts in higher education. But it has the feel of damage limitation in a fairly narrow part of the HE sector while what we really need is an important public discussion about what – and whom – higher education is actually for.

In the absence of any clear government vision for higher education, or for the arts and creative industries for that matter, presenting a compelling case for strategic priority funding is, well, tricky.

A small pot gets smaller still

The SPG is the ever-diminishing grant funding that supports teaching in subjects with high delivery costs in HE, supplementing the income generated by student fees, which have remained capped at the 2017 level of £9,250 for UK students, despite inflation.

The subjects threatened with cuts are mostly performing and creative arts and media, and the sums are already meagre: £16.7m for the sector will go to support creative subjects from the total SPG of £1,456m, of which about £450m is capital funding and the rest supports teaching costs.

So, less than 2% of the teaching grant is currently allocated to non-STEM subjects, reducing in real terms year-on-year since it was halved to the current level by Gavin Williamson when he was Secretary of State.

Nonetheless, the letter represents a further blow to morale and will make the celebrated diversity of practice-based provision in creative subjects impossible to maintain. As I write, more than a third of Higher Education providers are making redundancies and the strategic priorities set out by Gillian Keegan will seal the fate of many who have somehow survived the perfect storm of Brexit, Covid and the widespread removal of creative education from the school curriculum.

International students and partnerships have provided an essential lifeline, drawing on the two key dimensions of the UK’s leading global reputation for both higher education and creative industries. Current policy to curb international students as a way of reducing overall immigration figures will not help matters, to put it mildly.

Considering competing public priorities

I’m not a neutral bystander. As a Professor of Theatre, I’ve been a Deputy Vice-Chancellor and Dean of an Arts Faculty and have faced tough decisions at executive level in HE over many years. In my field, debates about funding and value are certainly not new.

I recall a salutary discussion with my then Head of Department, the wonderful James Redmond, from my days as an undergraduate at the University of London. (I left Cambridge, where Drama wasn’t regarded as an academic subject, for Westfield College (University of London), now QMUL – which is one of those universities making staff cuts in its English and Drama department.) It went something like this: “If I have a heart attack” said James, “I won’t want a drama graduate, I’ll want a trained doctor.”

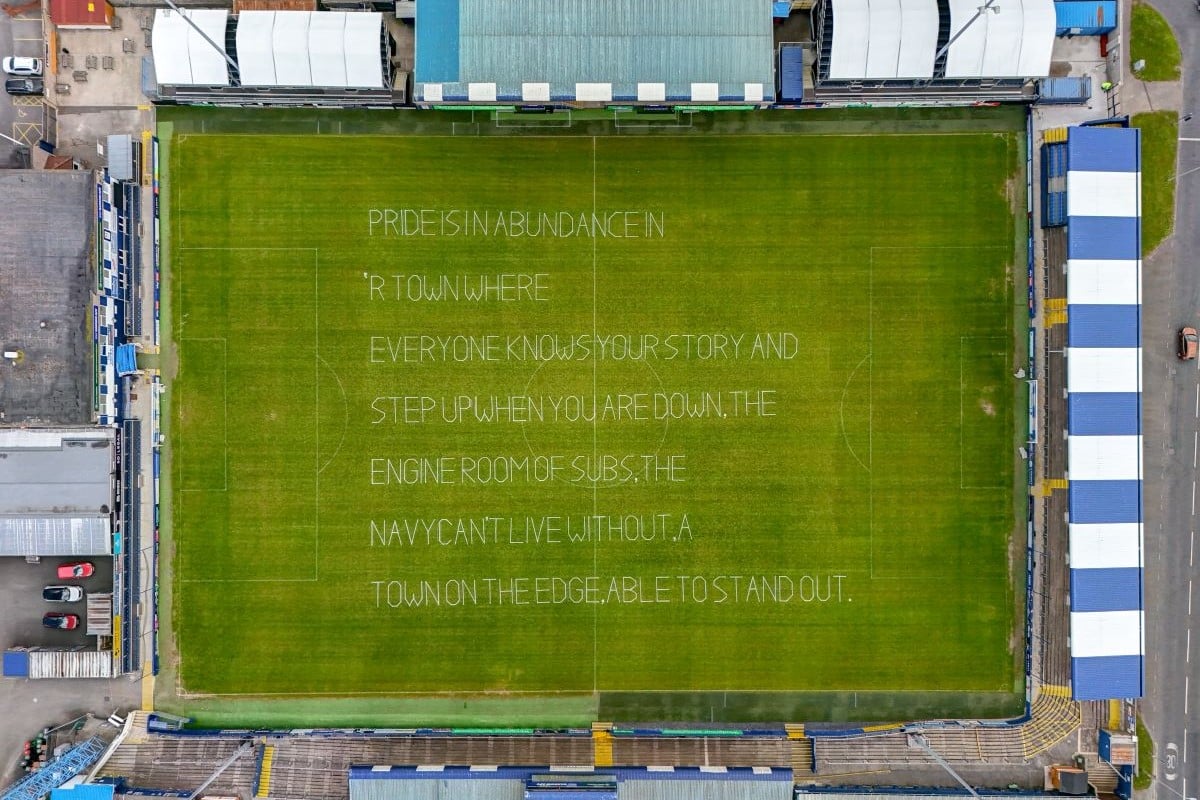

Then again, as an early career academic at Hull University in the 1990s, I used to invite students to consider the dilemma in Scarborough at the time, where the closure of public lavatories was being weighed in the press against local authority funding for the Stephen Joseph Theatre. When there are finite resources, the cost-benefits in the short, medium and longer term need to be debated. That’s how strategic priorities are formed.

In both these examples, the underlying question is about the public good. A doctor doesn’t serve just one patient, but many. Public facilities serve a whole community. The arts at their best aim to be inclusive, with an ever-widening reach. And in neither of these examples are the benefits primarily financial.

And yet, replacing vision and long-term strategy with regulation and short-term measures, the desired outcomes for teaching in universities have been recalibrated since the establishment of the Office for Students (2018) as a consumer protection body, “placing prime emphasis on promoting the interests of students” and “explicitly champion[ing] the student, employer and taxpayer interest in ensuring value for their investment in higher education”.

All the benefits, less of the costs?

Over my career, the emphasis in teaching in universities, at least in terms of accountability if not culture, has shifted from creating public good to ensuring individual cost-benefit, based on employment and salary – much easier to measure than more nebulous societal qualities.

Students whose degrees don’t earn enough to repay student loans – most arts and humanities graduates – are deemed to be underserved by HE. The funding of arts students – an effect not of the paucity of their education but of the perilous landscape for employment as a creative practitioner – is embarrassing to a government that cannot balance the books on student loans.

These students are therefore identified as a burden to the taxpayer, regardless of the non-financial benefits they may derive for themselves or the huge benefits they generate for wider society using the skills, experience and knowledge they gained in HE.

Whether these benefits are in innovation of new products, services and experiences, supporting other industries and services, improving education, health and wellbeing, creating everyday environments or ensuring social cohesion, the “value for their investment” has to be measured in terms that go far beyond the earnings of the individual graduate.

So the key question for me is not just about reframing the argument for funding of the arts and creative industries – although that remains an occupational necessity. Keegan clearly gets “the considerable cultural, societal and economic benefits” of high-quality arts education.

She knows the creative industries sector was the fastest growing part of the economy and has report after report to confirm the benefits. But the government seems to have made a choice to reduce costs by taking high-cost creative arts subjects out of universities, while seeking to retain the benefits of the UK’s successful creative industries.

With the reduction in arts education in schools, and the limited success to date of creative apprenticeships, it is hard to see where future generations of creative professionals will learn. Or how the interdisciplinary innovations on which our future so depends will come about, with only the small specialist institutions to uphold virtually all the advanced education provision for such a huge and diverse sector.

And I haven’t even mentioned research. Or diversity.

We need to talk about Higher Education

The pressing question now is why these subjects should have a place in the future of higher education beyond the “world leading small and specialist” institutions for whom £58m of funding is ringfenced in the letter, given that most students will never earn enough to repay their loans.

There is a real need to find a public forum for a wide-ranging debate, one where conflicting priorities and values can be brought together and teased apart, where fraught questions of resource and capacity, privilege and access can be argued out. And where the costs and benefits can be understood not just in terms of salary data and often conflicting targets of separate government departments, but in terms of a vision for the kind of world we want to live in, and what we want our universities to do to help create it.

Maybe the only way we can have that discussion is with the help of artists themselves.

Professor Carole-Anne Upton is Vice-Chair of the Board of LAMDA and former Deputy Vice-Chancellor of Middlesex University.

![]() lamda.ac.uk/

lamda.ac.uk/

![]() @LAMDAdrama | @uudramaqueen

@LAMDAdrama | @uudramaqueen

![]() carole-anne-upton

carole-anne-upton