The Competition & Markets Authority is investigating Ticketmaster over its sale of Oasis tickets

Dynamic disaster? Lessons from the Oasis ticketing row

With headlines raging around Ticketmaster and Oasis, will there be fallout for arts organisations that price dynamically? Robin Cantrill-Fenwick thinks it’s time to get ahead of a growing conversation.

Last year a ticketing company invited me to write about the power of dynamic pricing to grow revenue and to act as a positive force for audience diversification and development. There was a problem: I only believed half of that premise.

Dynamic pricing is a powerful tool for making more money, but it’s quite a stretch to say it’s useful for much else. Of course, the higher the overall ticket revenues, the more accessible an organisation’s programme may be when viewed in the round thanks to cross-subsidy. The high-value work supports other activities.

How compelling that argument is when, as an audience member, you find yourself consistently priced out of blockbuster musicals but regularly offered deals on less in-demand work, I’ve never been completely sure.

To their credit, the ticketing company asked me to write what I believed – and so among other things I wrote “dynamic pricing really works best when it’s simple and fairly opaque – and the signs are that’s a growing problem for some regulators”.

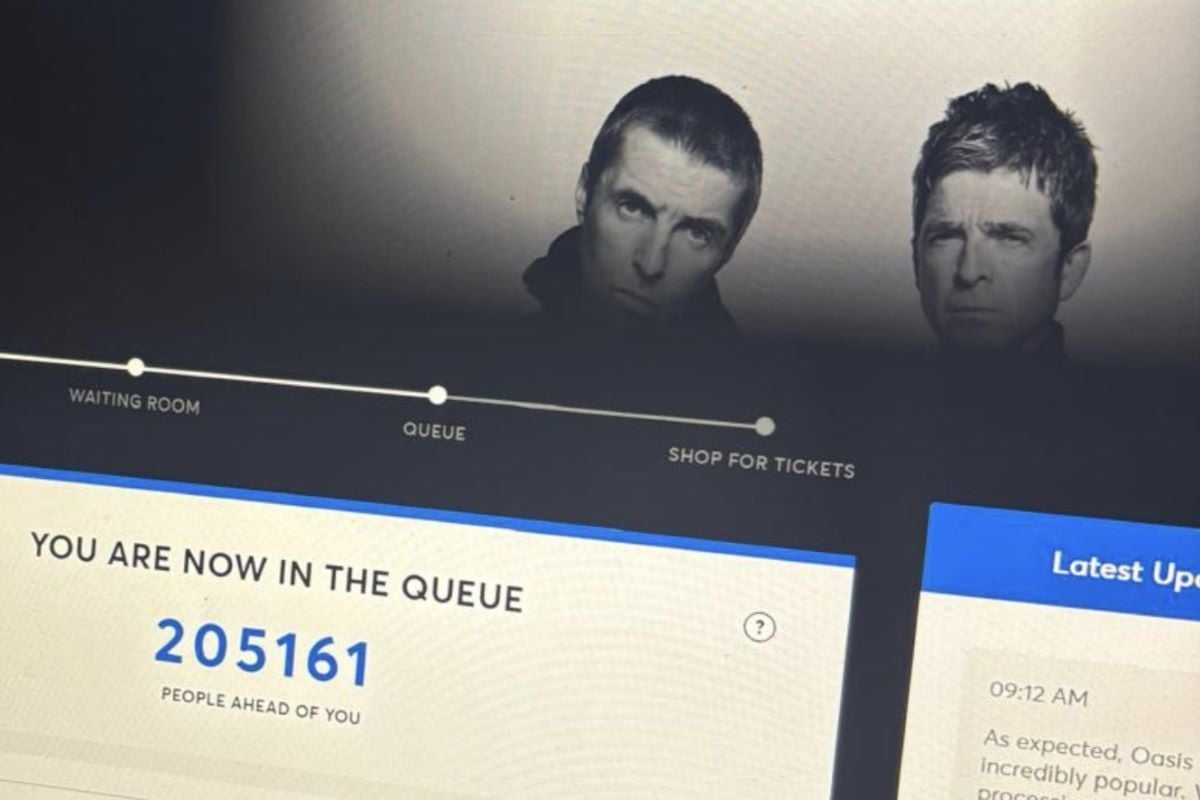

So the Oasis/Ticketmaster kerfuffle, and the reaction from regulators and consumer groups, comes as no surprise.

What went wrong?

How concerned should arts organisations be about the growing regulatory and pressure-group interest? I have a short list of ‘tripwires’ which tend to expose dynamic pricing to criticism:

- A fast speed of sale is used as a signal to increase prices with similar speed

- The top end of prices is stretched, and the advertised highest prices end up shocking the average consumer

- The number of adjustments is so frequent the price lacks stability in any given moment

- The value exchange becomes irrational, where the last seat (or standing place) to be sold sells for more than the best seat in the house, or a premium package

The Oasis on-sale arguably tripped all of these and threw in the time pressures associated with great scarcity of supply.

Arts organisations are usually more restrained. An arts organisation refining a price by 10% or 20% is one thing, but when concert prices are adjusted by more than 120% in a known-high demand situation, that’s quite another. We may all be dynamic pricing, but we are not all dynamic pricing in the same way. We may need to make this case clearly in the coming months.

Where dynamic pricing works

The strength of dynamic pricing for the ticket seller is also its greatest regulatory weakness. From the consumer’s point of view it’s opaque. It tilts the field in favour of the seller by ensuring only the vendor knows how high or low a price might go, where the thresholds for price change are, and on what schedule the algorithm or manual pricing adjustments are run. This uncertainty, even when the consumer is aware of it, drives increased conversion.

Dynamic pricing is most defensible when demand is uncertain, and when the market’s willingness to pay is elastic. Arguably it should not have been used for the Oasis on-sale, as it was clear the performances could sell many times over. Other than making a lot of money – almost certainly the main objective – all it achieved was to generate a slew of bad press, to make a joke of the published prices, and to leave some customers who got tickets apparently as unhappy (for now) as those who missed out.

Using ticket sales data from many different organisations, it’s clear that once dynamic pricing kicks in and starts changing the on-sale price, a clear majority of subsequent sales are above the on-sale price – i.e. more expensive.

Given the ratio of increases vs decreases it’s a technically correct, but ultimately weak, defence to argue that dynamic pricing lowers prices as well as increasing them. It’s a risky message to promote when consumers already feel misled.

What to do?

As a sector that prides itself on being audience-centred, we should celebrate our audience’s consumer rights. And those rights are best served through increased price transparency.

Often when setting dynamic prices, ticket sellers will choose an on-sale price and specify both a floor/base (the lowest the price can go) and a ceiling (the highest price). Without heavily affecting the conversion rate at checkout, sellers could make examples available on their primary ticketing website to illustrate their most typical prices. Where a queue is operating, this information could be linked to from the queue to help set expectations.

In the same article referred to above, I wrote: “Though dynamic pricing is often presented as new, sophisticated, modern and advanced – and it can be all of those things – it can also be inflationary, unnecessary, expensive, confusing, time-consuming and annoying.” So, the second thing to remember is that no matter how bombarded you are with sales messages, dynamic pricing simply isn’t always necessary – make sure you understand the criteria for when you switch dynamic pricing on and off.

If you consistently apply dynamic pricing to highest-demand performances, is that in the long-term best interests of engaging your total potential audience? If you’re not applying exclusions to more affordable price bands/zones, should you be? And is there genuinely good availability of more affordable seats?

In 2022, Baker Richards conducted UK-wide research which told us ticket buyers didn’t much like the sound of dynamic pricing, but were OK with it if it meant prices were going down! At the peak of the cost-of-living crisis, this came as no surprise.

But we also found people were surprisingly unaware of the practice. So, my third thought is that, in a mixed programme where dynamic pricing is only being applied to some events, it is most transparent to include a label to indicate when dynamic pricing is being used.

This need be no more prominent than a product-placement warning – which takes me to my final point.

Google Trends data shows that interest in dynamic pricing experienced a huge, five-year spike this month. Dynamic pricing had a chance to make a good first impression and, thanks to recent headlines, utterly flunked it. From rising star to toxic brand in a moment.

My final piece of advice is to avoid using the words 'dynamic pricing' for a good long while. Whether you call it adaptive pricing, plan-ahead pricing, or just early booking discounts, it’s best to find new language. Increased guidance or regulation to strengthen the rights of consumers is inevitable – we can either wait to be required to change or, as an audience-focused sector, we can lead the way.

Robin Cantrill-Fenwick is Chief Executive Officer at Baker Richards.

![]() baker-richards.com

baker-richards.com

![]() @BakerRichards | @RobinComms

@BakerRichards | @RobinComms

Robin will present Dynamic Pricing on Trial at the Northern Ireland Tourism Alliance Annual Conference on 26 September 2024. He will also present new data on ticketing for households on very low incomes at Ticketing Professionals NYC on 3 October 2024.

Join the Discussion

You must be logged in to post a comment.