Heffernan says the government must strengthen copyright law to provide artists with fair remuneration and a safe online environment

Photo: Eva Almqvist/iStock

Consultation on copyright: Doing nothing is not an option

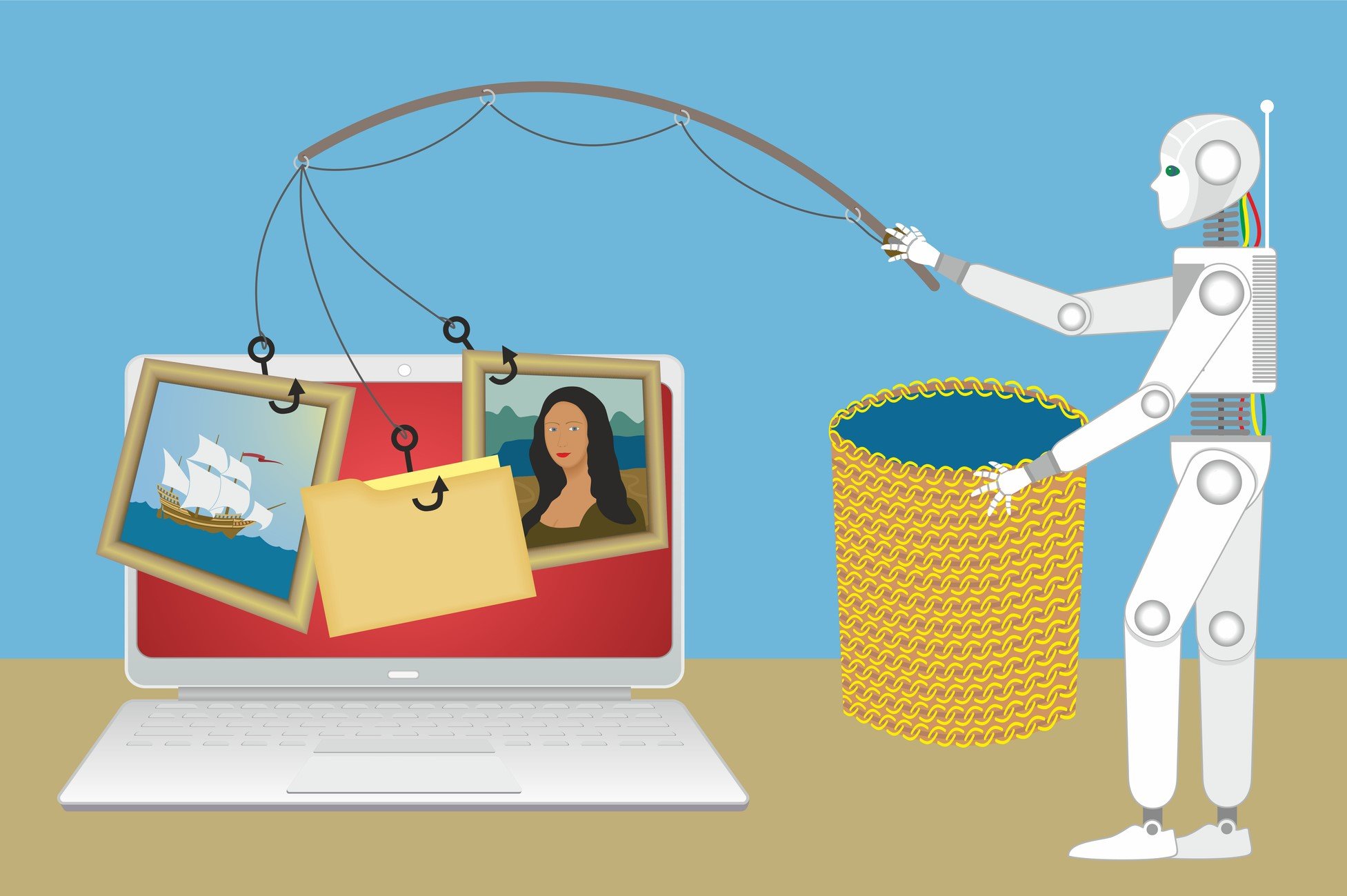

Scraping artists’ work is like automating shoplifting, says chair of DACS, Margaret Heffernan. She argues that current copyright law is woefully inadequate in protecting artists’ rights.

In December, the government opened a public consultation on copyright and AI. Ever since ChatGPT bounced onto the scene, writers, musicians and visual artists have had to come face to face with the reality that this new technology is acquiring its ‘intelligence’ by scraping their work.

In effect, this means several things:

- The gigantic value generated by AI companies owes a huge amount to work done by others who are being paid nothing.

- Copyright protection exists the minute a musician, writer or artist produces a work; no formalities are required. This makes it a beautifully easy system to enforce. But AI flouts that law each time it scrapes an artist’s work; it’s like automating shop lifting.

Artists’ ability to earn income from their work is threatened by AI’s capacity to generate a limitless number of derivative works. When the scriptwriter Alison Hume found the subtitles of her TV scripts had been scraped, she knew they could be used to generate scripts without her. Her legal rights have been violated, her future earnings threatened, and the BBC can’t protect the work they paid for.

Automated out of existence

Since the advent of AI, all kinds of artists have seen work and jobs evaporate. In music, the writing of jingles for commercials – once the traditional entry-level work for young musicians – has been automated out of existence almost overnight, while the number of jobs creating images fell by 35% between January 2022 and July 2023. Copywriting work too, which once sustained aspiring writers, is giving way to automated menus of snappy choices.

Of course, artists are up in arms. The government consultation proposes three options:

- Doing nothing.

- Strengthening copyright, requiring licences in all cases.

- Allowing artists to opt out of their work being used for AI.

Doing nothing is not an option. Current copyright law is inadequate and the courts are swarming with costly lawsuits. Opting out turns copyright law on its head, requiring artists to protect each work every time they make one. It replaces an easy, elegant system with a bureaucratic process with no workable means of implementation or enforcement.

The choice should be simple: strengthen copyright law to provide artists with fair remuneration for their work and a safe online environment where it is protected.

Instead, the argument is being framed as a false binary: give the AI titans whatever they want or the UK will lose the AI race. Minster for Science, Innovation and Technology, Peter Kyle, argued it would be a disaster if “young people… who aspire to work in technology” should have to “leave the country and work abroad in order to fulfil their potential”, just because artists cling to their right to legal protection. Sure, he conceded, artists are ‘emotionally’ attached to their work – but economics matter more.

Absurd misrepresentation

This is absurd misrepresentation. Nothing could be further from the truth. I’ve spent my life in media and running technology businesses. The mindset which sees technology, engineering, mathematics and science as one kind of serious, disciplined, intelligent, valuable activity and the arts as frivolous, emotional, as some kind of peripheral, infantile activity could not be more wrong.

The musician Soweto Kinch said it’s common for people to think of the arts as “a bit like dessert: unnecessary and probably bad for you”. But artists, scientists and technologists themselves see this quite differently.

Artists aren’t afraid of uncertainty, they move towards it, just as scientists do, knowing that is where new discoveries are to be found. Both know that doing so is risky, challenging and unpredictable – which is why they do it.

They can handle complexity and ambiguity because that’s where new meaning, insight and invention is to be found. Both are excellent at innovation which requires all these qualities. That all of this is difficult to do and to understand. Well, for artists, scientists and engineers alike, that’s the draw.

Artists among society’s most resilient

I’ve worked alongside musicians, writers, performers and visual artists for a long time and I’ve spent the last two years interviewing them about the creative process. These are some of the most disciplined, tough, courageous, insightful, fearless, resilient people in our society.

They start work before being asked, show initiative and don’t quit when it gets hard. Driven by curiosity, they develop whatever new skills a new project demands. Trained to be self-critical, they are both imaginative and analytical.

I also work with CEOs of global businesses. One of their biggest concerns? “We hire well credentialed people, from fine schools and universities and they are good at doing what they are told. Following instructions. But when we turn to them for creative thinking, they’re lost. It isn’t what they’ve learned. I’m not sure what we will be able to do with them when they’re 35.”

Everywhere I go, the cry is for people who can think for themselves, come up with novel solutions, imagine different, better ways to get work done.

Don’t denigrate the arts as ’emotional’

Looking at the most recent World Economic Forum Future of Jobs Report, analytical and creative thinking remained the most important skills for workers in 2023. In 2024, employers told Forbes that creative thinking is the most in-demand skill. The National Foundation for Educational Research studying the need for skills in 2035 named as the five most vital: communication, collaboration, problem-solving, planning and organising, and creative thinking.

That’s what artists do all the time – and more. They are the skills that making art, of any kind at any level, can develop in us all. And we need the whole ecosystem of the arts – the teachers, the libraries, the museums, galleries, auction houses and concert halls – to keep them in every aspect of our lives.

This is what happens when you cut the arts and humanities out of the education system. When you denigrate it as ‘emotional’, discretionary, soft, indulgent. When you instigate criterion-based assessment, which grades an essay according to how closely it approximates to the ‘model’ answer.

When you penalise students for imaginative responses to banal assignments, you get obedient, compliant people who have learned not to think for themselves. You lose creativity just at the moment it is needed most. That is the bigger economic, political and human rights failure the UK faces now. We all have a stake in it.

Embracing Uncertainty by Margaret Heffernan is published on 25 March.

Join the Discussion

You must be logged in to post a comment.