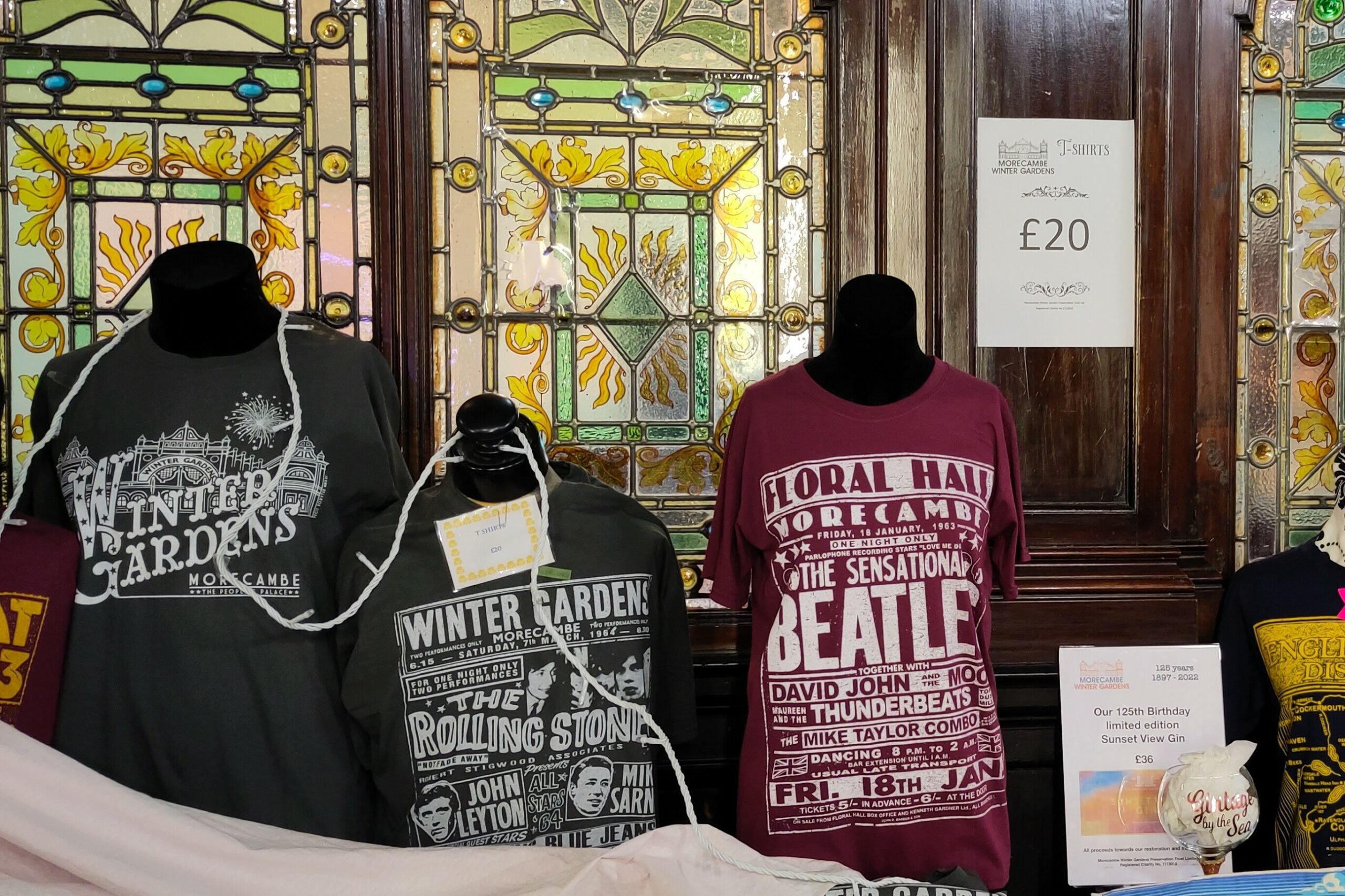

Merchandise stand at Morecambe Winter Gardens

Photo: Jason Jones-Hall

The business model of place

With the Chancellor’s Autumn Budget committing to an as-yet-unspecified ‘package of cultural infrastructure funding’, Jason Jones-Hall unpacks some of the learning and challenges from existing capital schemes.

In my last article, I discussed the importance of developing a partnership mindset, and how powerful it can be when all partners are united around a shared vision of creating a better place to live, work, study and visit – and how this can help unlock significant levels of place-based funding.

So let’s say that’s happening – and at Five10Twelve we work with plenty of places where it is, most notably through the Cultural Development Fund (CDF) Network. Everyone working together. All driven by a common goal. Multi-million-pound regeneration funding in the bag. Everything in place to make sure that new shiny new capital project or heritage site refurb goes ahead … right? Just one thing: who is going to keep it running?

Throw a stick far enough anywhere in the country and there’s a good chance it might land on any one of a number of recipients of a Levelling Up Fund, Cultural Development Fund (CDF) or Towns Fund dealing with this challenge. Making a great place to live, work, study and visit sounds good in a strategy document, but it is not in itself a business model for a single capital project.

Market failure

The business model of place is complicated, precisely because it is tied to this idea of a shared vision. The vision says that if the place does well, then the businesses – or venues – within it will naturally grow and thrive. This may be true, but it is inevitably a long-term, distributed model of growth that does not help the single capital project that is expected to kick-start the whole process. Nor is it easy to capture, measure or directly attribute to that project.

The golden principle of public funding is that it is needed where there is market failure. In other words, there is a perception that the large-scale new creative hub or cultural centre may not be commercially viable because the market does not exist for it – or perhaps not yet.

But while the ‘if you build it, they will come’ approach might work conceptually for local or national government, whose needs are to regenerate a town or provide a facility for the community, it may not be enough to convince an operating partner, whose primary needs are to turn a profit or ensure sustainability of their organisation.

Commercial viability

Recent capital funding for such projects invariably comes with one significant string attached: make it commercially viable. The desired outcome is to kick-start regeneration on a town or district level, but required outputs are tied to the project as a standalone entity and they are invariably economic: business inceptions, jobs creation, apprenticeship starts – all of which require revenue growth.

So local authorities – or cultural organisations – tasked with delivering these projects are expected to succeed where the commercial markets fear to tread. That’s quite a burden.

While large-scale capital funding initiatives may deliver that new or repurposed building, this doesn’t mean they can create or stimulate a market for that new building all by themselves, without which it simply isn’t operationally sustainable. This is, after all, the market failure that created the issue in the first place.

There are no simple answers. But the first three rounds of CDF Network projects provide plenty of learning around what does, doesn’t or might just work, a tiny glimpse of which is presented here.

Revenue funding

This is crucial to help seed the market, create and build partnerships, engage local communities and activate buildings and spaces. This can be built into the capital fund itself – CDF is a good example – or capital projects can catalyse and unlock revenue funding from other sources – eg Heritage Fund, Shared Prosperity Fund, High Streets Heritage Action Zones etc.

Issues here are around the project management and administrative burden this places on the delivery partners. How can national and local government and/or funding bodies help support these partners or streamline reporting requirements for multi-funder projects?

Non-commercial operators

Perhaps serving as examples of Lisa Nandy’s Civil Society Covenant in action, there are several examples within the CDF Network of local authorities, community groups, NPOs and volunteer-led organisations acting as delivery or operating partners, including in the Isle of Wight, Bradford, Morecambe and Torbay.

The drivers here tend to be around operational sustainability rather than turning a profit, although this in itself comes with its own challenges and can place a heavy burden of risk on the sustainability of the organisation itself.

What support do these organisations require, beyond just capital or revenue funding? This is about skills development, capacity building, supporting good governance and developing local leadership.

Removing the burden

If community ownership or non-commercial delivery is part of the answer, this also means removing the burden to deliver the kind of hard economic outputs that the market failure conditions which prompted the funding in the first place have shown to be unrealistic.

More realistic output requirements must be explored, recognising that the benefits may be around addressing broader issues – e.g. health, wellbeing, education, community cohesion.

If there are economic benefits, these will be felt in the longer term and distributed across the whole region rather than in that one single project. The work that Harman Saggar and his team at DCMS and AHRC is doing on Culture and Heritage Capital is a crucial part of this.

Regeneration is the answer – so don’t change the question

The wider business model of place also means having grown-up conversations with town planners and developers. Round one CDF project, Creative Estuary, is a great example.

As a sector, while we may sometimes be victims of our own success in suddenly facing hikes in rent and operating costs as regeneration kicks in, but we cannot continue to wear the hand-crafted hair shirt knitted from unreasonable accusations of artwashing and gentrification.

This is undeniably a complex and challenging issue, but it’s not one for us to solve. There is an inherent unfairness in expecting culture to make better places to live, work, study and visit … but let’s not make it too successful, shall we?

Operational sustainability, viability, building legacy through revenue programmes and shared learning from CDF projects will be at the heart of the agenda for the second CDF Network Symposium, scheduled to take place at the magnificent Rochdale Town Hall on 26 March 2025. Full details to be announced soon.

Join the Discussion

You must be logged in to post a comment.