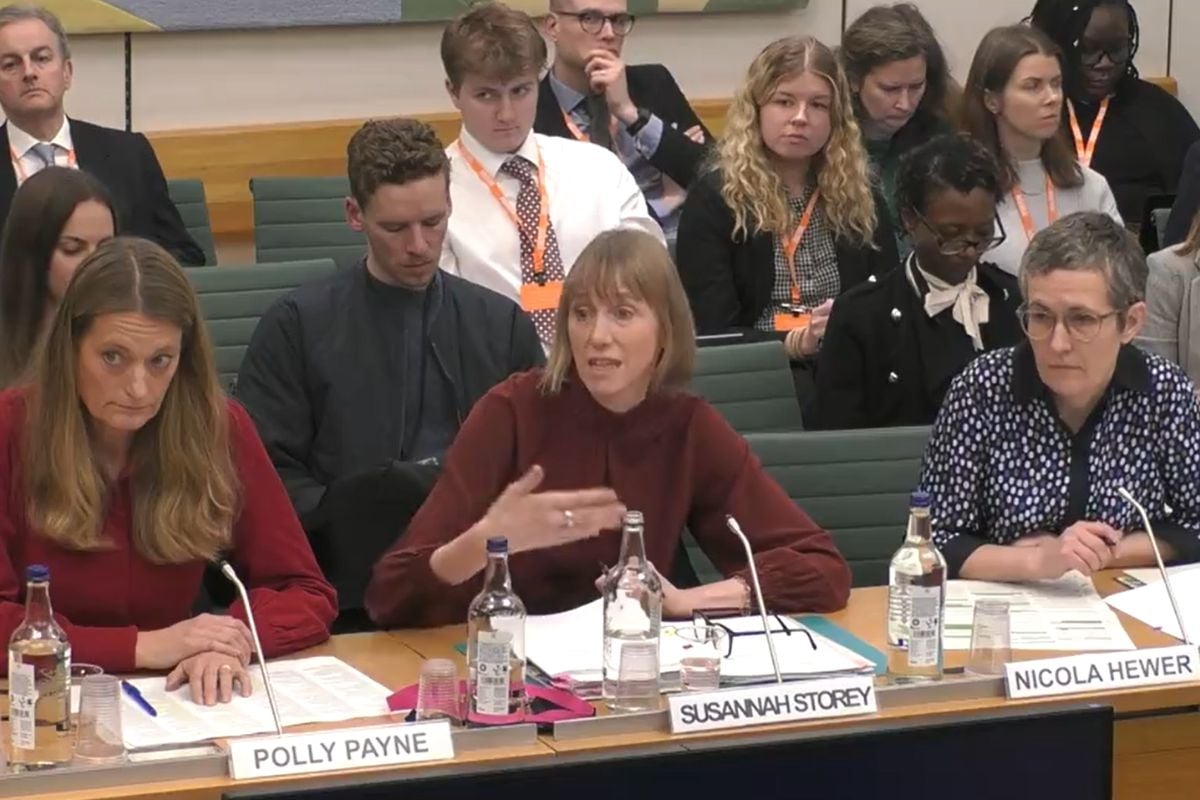

Senior civil servants Polly Payne, Susannah Storey and Nicola Hewer gave evidence to a Public Accounts Committee hearing scrutinising management of Covid loans

Photo: Parlimentlive.tv

DCMS faces questions on Covid loan book ‘conflict of interest’

MPs have raised concerns over Arts Council England continuing to act as a loan agent for Department for Culture Media and Sport, when there is a risk the funding body may have a vested interest in the survival of the organisations making repayments on Culture Recovery Fund loans.

Senior civil servants have faced scrutiny from MPs over whether the management of the Department for Culture, Media and Sport’s Covid-era loan book could be at risk of “a conflict of interest” that will “get worse going forward” as more organisations are due to begin repayments this year.

Speaking at a Public Accounts Select Committee hearing on Monday (10 February), Luke Charters was one of several MPs who asked DCMS staff if there was a conflict of interest in having arm’s-length bodies Arts Council England (ACE) and Sport England continue to act as loan agents for arts and sports organisations whose survival they might have a vested interest in.

“There’s a great paradox here between the policy objective and the financial objective,” said Charters.

“The policy objective being you want to ensure the survivability of these institutions. The financial objective being you want to recoup the capital and interest the taxpayer. But that means that you are constrained in things like how you manage the loan book.”

Policy vs financial objectives

The committee examined DCMS’s handling of Covid loans awarded from October 2020 to March 2022. Totalling £474m to 120 borrowers, this is the first time the department has managed a significant loan book.

During the pandemic, a total of £256m went to 37 culture bodies through the repayable finance strand of the Culture Recovery Fund, with loans issued on an average term of 15 years and almost all charged at 2% interest for the entirety of the loan period.

Along with Sport England, ACE was appointed as a loan agent, responsible for the day-to-day management of the scheme and relationships with their respective borrowers, although all decision making remains with DCMS.

Polly Payne, co-director for general policy at DCMS, said there were two safeguards to address any “tensions” between financial and policy objectives, including having “discrete teams” within ACE and Sport England who deal with borrowers to “maximise the return for the taxpayer”.

Secondly, she said DCMS had been “absolutely clear” that in any situation where a decision might be made that isn’t in pursuit of a financial objective, such as offering more favourable terms to an organisation that was struggling to make its repayments, it could only be made by ministers.

“So for instance… if you had a cultural organisation which was in an area that was otherwise a cold spot for cultural activities… it might be something that ministers thought was a good use of taxpayers’ money to give a subsidy to, and [ministers] would have to make that decision,” said Payne.

‘A risk of borrower advocacy’

Despite the committee repeatedly asking whether, upon reflection, another part of government should have been handed the task of running the loan book down, DCMS permanent secretary Susannah Storey disagreed and appeared reluctant to concede there was any conflict of interest in the scheme.

“I see that you are sensitive about whether there is a conflict of interest or a tension,” committee chair Sir Geoffrey Clifton-Brown said to Storey.

“And I think this—whether it is a tension or a conflict of interest— will get worse because I suspect that more organisations will go bankrupt and more organisations will not repay their loans at all or on time.”

To date, nine borrowers, two in culture – Supply firm Energy Generator Hire Limited and Nottingham Castle Trust – and seven in sport, have fallen into insolvency, with loans totalling £46.1m.

The two culture cases account for £2.5m of the total losses, and DCMS does not expect to recover anything from those organisations.

In response to Clifton-Brown’s line of questioning, Storey said that while there is “always a risk of borrower advocacy”, she did not think it was “unmanageable”.

‘There is no money anywhere’

With repayments on all Covid loans due to begin this year, a number of cultural organisations have voiced concerns about coping with the extra financial burden.

Last month, the British Council revealed that its efforts to get the government to accept its £200m art collection to pay off its outstanding Covid loan had failed, leaving its long-term future in doubt.

The council’s loan is not part of the Culture Recovery Fund, and the government is charging commercial interest rates with a rolling one-year term, which the council has said will leave it struggling to meet the repayments.

Meanwhile, co-artistic director of the Royal Shakespeare Company, Tamara Harvey, has cited the organisation’s £24.4m Culture Recovery Fund loan as contributing to the “huge financial challenges” the company is facing.

The RSC will need to make its first £1.2m instalment this year and won’t pay off the debt until 2040.

Speaking to The Times alongside co-artistic director Daniel Evans, Harvey said the situation was “really hard”.

Evans added, “We have had conversations with the government about whether we really do have to pay it back.”

“We do. There is no money anywhere, the government needs that money too. We get it. So it is really tricky.”

Join the Discussion

You must be logged in to post a comment.